C L E A R I N G

is pleased to announce

MY INTERESTS

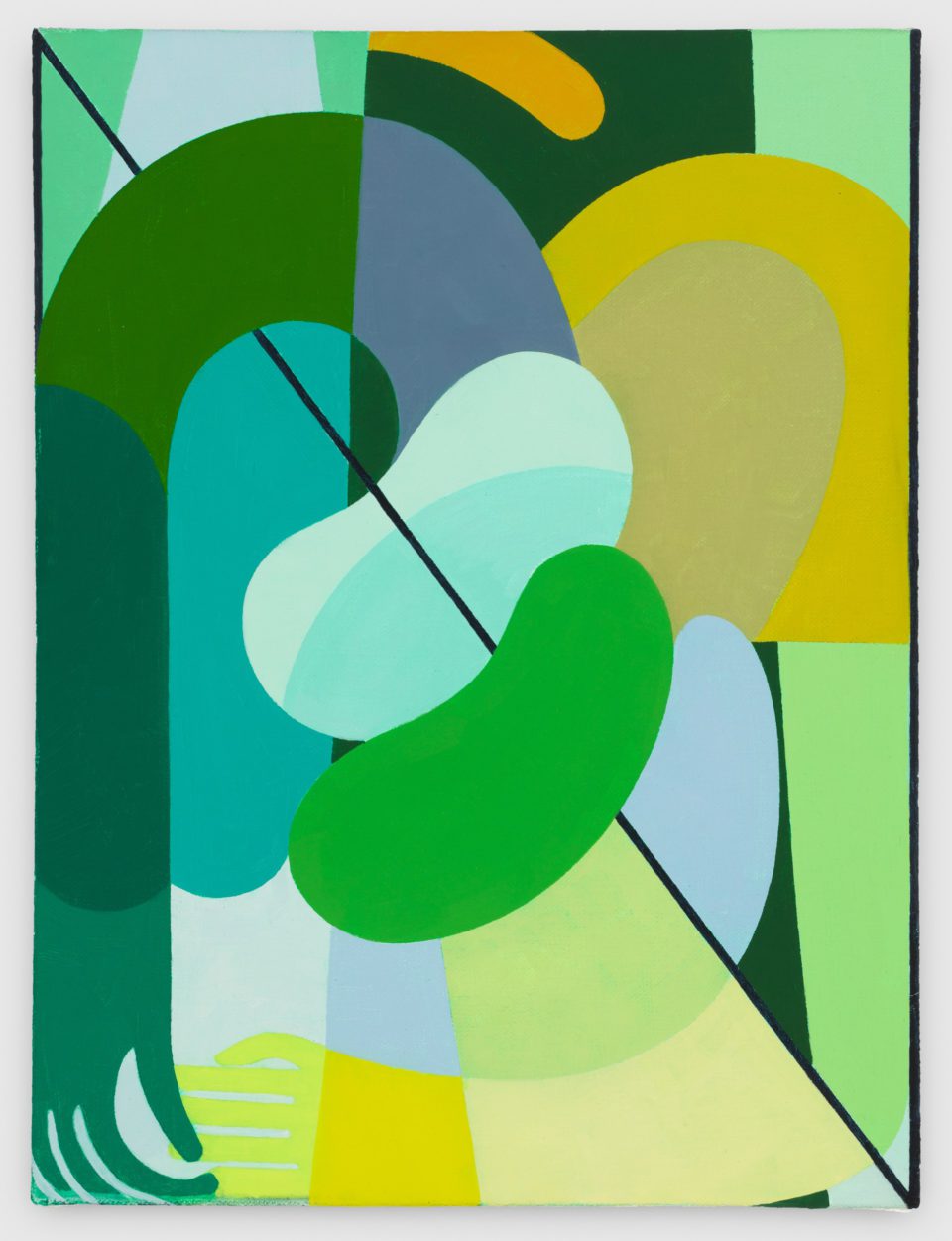

An exhibition by Sebastian Black

September 8, 2017 - November 4, 2017

C L E A R I N G, Brussels

M. made one painting of Obama for every day of his presidency. Hard to say why. Let’s leave aside the painting’s shared subject and first address the parameters of the project. The massive number of paintings is immaterial on its own. What is important is that it corresponds to the number of days Obama occupied the oval office. If there had been a few more paintings than days or vice versa, that is, if over the last eight years M. had simply spent most of their days working on paintings of Obama their activity would have constituted something like a practice. Instead M. finished exactly one painting per day over a predetermined series of days. So circumscribed [head] their activity could be called a project.

This project-ification of practice is a frequently deployed aesthetic strategy among contemporary artists seeking proximity to Conceptual Art’s historical prestige. Within it the conceptual becomes a mood, an abstraction which can be produced or appropriated via set dressing. Aesthetic decisions formerly made in the service of a radical concept become themselves “conceptual”. They become ornaments whose decorative function is to recall their own art-historical precedents. Perhaps more perniciously, a simplistic relationship between the concept and the material in which it finds expression is taken up and reiterated. Here the concept is posited as transcendental, a preexisting entity, somehow external to the medium in which it arrives.

In the exhibition of M.’s Obama series we saw many of conceptual art’s most thoroughly reified aesthetic legacies utilized. The installation consisted of two large storage shelves which occupied most of the gallery floor [eyes]. These contained hundreds of identically sized paintings [pupils]. At the periphery, the walls were covered from floor to ceiling with as many of the paintings as could fit. While the central domineering display mechanism obscured the actual faces of approximately two thirds of the canvases it hammered home the supposed vastness of M.s undertaking. More fundamentally, it foregrounded the importance of the general series over and against any particular work. Lastly, it situated the whole endeavor within quasi-bureaucratic mis-en-scene.

Setting the stage thus in some respect allowed M. to have their cake and eat it too. On the one hand it became easier to leave aside the artist’s relation to their subject matter – a state of affairs uniquely beneficial to M. – for we were presented with the model of artist as a disinterested administrator of the free floating concept. Meanwhile the insistence on the sheer amount of paintings highlighted precisely those bourgeois hero myths about artistic labor which such models once attempted to undermine.

The show’s press release, a spare two sentence [ears] account of the parameters of the project ended with the number of paintings produced. 2,922. Since the exhibition’s supplemental discursive material was largely self referential viewers were right to assume that the reason M. made all of these paintings of Obama was to communicate, “I made all of these paintings of Obama”.

A performative gesture which ultimately refers only to itself, M.’s exhibition became very close to another performative act, namely the egocentric self-narrating speech acts small children use as means of individuation. For children these language games function at their core as a way of simply saying “I speak,” thereby affirming their existence as an “I”. Paolo Virno calls the statement “I speak” the absolute performative, for while similar utterances in the adult world provide partial analogs such as a promise (i.e. “to say: I promise”) no utterance so perfectly encapsulates itself as “I speak” (i.e. “to say: I say”).

For adults this absolute performative is manifested most closely not in promises, legal procedures, blessings, curses, or any of the other ritualistic speech acts we practice on a day to day basis but in prayer. Virno reminds us that “Representing oneself as speaker – prayer’s most important task and benefit – is also the foundation of the principle of individuation. . .” continuing “the necessity to emphasize or to reaffirm this individuation is only felt in times of crisis”. (Paolo Virno, When The Word Becomes Flesh, Semiotext(e), New York 2015, p. 86). The exhibition’s press release indirectly alluded to our own crisis. Besides telling us the number of paintings it is careful to denote the date of Obama’s initial inauguration in 2009. By doing so it called forth the then impending inauguration of the next president. The viewer was left to stew in the hypothetical ellipsis [whiskers].

The whole exhibition thus became a kind of prayer, an artistic act of individuation, which due to the institutional setting was also an exhortation to pray along. It is clear that M.’s aesthetic forbears are neither the conceptual artists whose shell he often dons, nor the modernists whose core he assimilates. Instead M.’s paintings most closely resemble pre-modern religious paintings. Like them M.’s works are not open. They do not rely on the disinterested reflection of a receptive audience, but rather mobilize affect to forcibly compel an audience’s interested participation in the production of a predetermined meaning.

During the run of the exhibition the hushed gallery recalled a chapel as much as any library stack or desolate archive and the paintings lining the walls became sequential frescos in an illustrated hagiography. I thought as much about the Holy Spirit, that white bird that dangles from the corner of the trinity [nose, mouth], as I did about any material political valence. But this is precisely the point. M.’s performance communicates little more than the fact of its own performance. In doing so M. follows an ancient formula which eschews worldly communication in its search for divinity. Simply put, through their art M. seeks proximity to power.

2017, Oil on linen, 36 x 24 inches (91.5 x 114 cm)

What an interesting time to see A Revolutionary Impulse: The Rise of the Russian Avant-Garde, at MoMA! The survey arrives in America at a moment when our liberal democracy is being intentionally dismantled. Our own forward thinking artists are entrenched in positions of negation against all sorts of destructive forces. So how should we read an aesthetic project with an unabashedly affirmative predisposition? Fertile juxtapositions abound!

Without necessarily advocating a turn towards state sponsored socialism, many on the left – and some on the right – are pointing out that capitalism is a system which erodes its own foundations.

If a few of these foundations are sustained availability of natural resources, sustained availability of human labor, and faith – in everything from the fetishistic magic of the smallest commodity to the innate reasonableness of the largest “invisible hand” – it doesn’t take long to see why their arguments are gaining currency.

Yet the impending collapse of capitalism doesn’t mean everybody is losing money. Far from it! Melting down a political-economic paradigm [head] affords many opportunities for short selling, for arbitrage, and the euphemistic transfer of public money into private coffers through “partnerships”, “charters”, “right to work” laws, etc. In fact the degree to which these techniques are elevated to philosophies of governance in their own right provides a useful metric to assess the state of our union.

The virtues of these techniques were most memorably espoused by Gordon Gekko in the 1987 movie Wall Street. It’s fitting that Carl Icahn, the infamous “corporate raider” on whom Gekko was largely based, is now set to become a senior adviser to our new president. Ironically, Icahn is one of the few high profile cabinet appointees whose professional resume does not inversely correlate with the stated aims of his new post. It is safe to assume that under his influence “regulatory overhaul” will be robust. The federal government is stripping itself for parts. The donors are furnishing their bunkers. The violent blend of self interest and fatalism that created our country now unwinds it.

And so the stakes are raised. It certainly feels like it anyway. Out of nowhere history comes thundering into the present. I wonder if a new art will come thundering along with it. Will a heightened historical awareness engender new aesthetic programs as it has in the past? What forms should we sanction? What colors? This is all to say: What are our means? And also: What are our ends? And then of course: Wait, should artists even have ends? Our uniquely convoluted relationship with function chafes away [whiskers].

It is clear that the constructivist artists could not have conceived of an aesthetic program without a functional valence. A Revolutionary Impulse represents a milieu where artists, designers, filmmakers, and factory workers made the stuff which would constitute the new world everyone hoped to inhabit. As a piece of this new construction an abstract painting was as useful as a pair of teacups [eyes]. Nursing my sores in this heady balm I think, “What an enviable historical circumstance that allowed for the affirmative production of objects whose aesthetic and political dimensions were coterminous!” Alas it was a circumstance that unwound in due course.

The failure of the communist project was not primarily an aesthetic failure but it has had aesthetic consequences for the objects that outlived it. Part of me sees the works in A Revolutionary Impulse as artefacts, those things whose specific purpose has been effaced by time. Ironically under the current aesthetic regime it is precisely this conspicuous lack that shores up an object’s decorative credentials. These clusters of formal means without functional ends look like art simply because looking is the only way to engage them. A trick of the eye renders their materiality abstract, their social dynamism inert. Beautiful posters line the walls but to many viewers cyrillic contours communicate little more than an ornamental sense of Russianness. Cracked surfaces [mouth] and sensuous facture invite even shadier methods of valuation. Ducking and squeezing between abundant contradictory evidence, the singular genius creeps back into our collective imagination. Oh how to rebuff his tiresome advances!

In a public conversation between the artist Dan Graham and the architect Itsuko Hasegawa the latter regretfully conceded that ”architecture itself is subject to conditions such as security laws and costs, and […] many social restrictions” He contrasted this to “Mr. Graham’s pavilions, [which] express something like an original form of architecture in a pure state with such restrictions omitted.” [Dan Graham and Itsuko Hasegawa, “Children Within Public Space”, in Nuggets: New and Old Writing on Art, Architecture, and Culture, JRP/Ringier, Zurich, & Les presses du réel, Dijon 2013, p.93]

The statement illustrates Hasegawa’s sympathy for the radically open ended nature of Graham’s sculptural program, a nature continually stymied in architecture by economic and material exigencies. That said, Hasegawa’s ideal form of architecture is not formalist in any strict sense. He does not posit an aesthetic practice which elevates pure form over attendant function in contrast to the functionalist ethos which dominates modern design. Instead, through Graham’s pavilions Hasegawa envisions a scenario before such distinctions were ever useful, a kind of primal constructivism.

It is no coincidence then that both men have designed spaces for children. Children are ideal clients for Hasegawa’s “original” form of architecture precisely because their play often subverts an object’s conventional use. How else can we explain the allure of the block? Even their own bodies are subject to imaginative appropriations; hands shapeshift into wings, claws, or pistols, often at the literal drop of a hat. Through a child’s intervention form and and function are rescued from their dialectical tension and returned to a state of symbiotic flux.

Standing with my back to a glorious wall of Malevich paintings [muzzle, nose] I saw a pair of boys walking arm in arm through the MoMA exhibition. Judging by their height and unselfconscious physicality I guessed they couldn’t be older than nine or ten. They loped around the gallery and stopped before an abstract painting by X. To my surprise they each gazed silently, transfixed. Then all of a sudden one of them chuckled. The other turned to his friend and asked “What’s so funny?” The laughing boy replied, “Oh, I guess you’re not up to that part yet.” Then they both cracked up.

Through his joke the boy had reactivated some truth about the painting’s unique relationship with time. Suffice it to say that for my two cents I’d like to make some forms which open to the ludic appropriations of children. Can a painting effect a new reciprocity between means and ends? On good studio days it feels possible. Though times are tough and resignation beckons, ironically, the question artists must again ask is : What’s the use?

2017, Oil on linen, 108 x 81 inches (274.3 x 205.7 cm)

It was damp autumn Saturday. I walked my mom down the gravel road to our mailbox (mouth nose). I asked her what a merger was, because on damp autumn Friday [muzzle] she and my dad were talking about Chase Bank and merger this and Chemical Bank merger that. The headlights were lighting forward and the tail lights were dragging backwards right behind us [whiskers]. The backs of their headrests [pupils] were inanimate silhouettes on the windshield (eyes). Night was all around us, and I let it touch my cheek through the car window. The next day on the road morning was all around [head] us. The pond was full and the frogs were in their mud huts. After the merger positions would change. People would move up and down and sideways and even out! Everything is change. I felt power from some loose live wire shock my little heart. Oh god of the merger! Oh god of the merged! How soft and honest and gray you were. You were there in the mud puddle, grasping my toes [ear].

2017, Oil on linen, 108 x 81 inches (274 x 206 cm)

A five year old draws a head [nose]. They add several eyes [whiskers] and a nose [mouth]. Then a horizontal mouth. They consider whether or not to add a mustache. Yes a mustache is a good idea, but does it go above the nose or below? The question is posed within the white paper rectangle [head] and its answer is hiding there too. Parents and teachers are not consulted. Referring to a “real” face is out of the question. Abstraction is this state of mustache suspension. It can be kneaded and stretched like pasta dough [ears] and this activity is what a lot of non five year olds mean when they say they practice art. When things go well the sense of having produced the present creates the illusion of freedom in one’s immediate past. This is what non five year olds mean when they say the word “new”. They mean a formerly opaque disc becoming as clear as a lens [pupil, eye], a frisbee disappearing into the sun [pupil, eye].

2017, Oil and pencil on linen, 84 x 63 inches (213.4 x 160 cm)

The galleries owe me money and I avoid checking my receipts when I’m taking out cash. If the atm flashes an account balance I jam the enter button to make it evaporate. I feel like a man without qualities [nose mouth]. I should lift weights. I should unwind in a bubble bath like supposedly all women (muzzle whiskers). I’m so mad I could crack a peanut shell! (eyes) I’m so sad I could peer into a well! (pupil) But then again I’m so afraid it might peer back (pupil)!

Someone from Merrill Lynch sent me a fruit basket this morning. It contained the world’s tastiest pear (head). How do those bastards do it? I had to use both my sleeves to wipe my chin (ears).

2017, Oil on linen, 84 x 63 inches (213 x 160 cm)

I emailed Rosemary Bellows to say thanks for the pear [head]. Also I said I’d like to divest from oil spills [head] and bullets [pupils] and multipage student loan agreements [eyes]. No sweat she replied, I’ll put your money into wind farms [nose mouth whiskers] and knit ties [ears]. I want to do well by doing good. Or is it the other way around?

2017, Oil on linen, 84 x 63 inches (213 x 160 cm)

Some young friends of the Guggenheim came to my studio. Though not quite peas in a pod we were certainly three dots in a box [head, pupils, nose]. In fact there was a painting on the wall kind of like that. The guy kept calling it metaphysical even though I kept telling him it was right there. His pal wore flowy silk pants [ears] which I kept calling ethereal. In light of recent political developments her fashion magazine was putting together an Art Issue reflecting on the legacy of Constructivism. In light of other developments my interests included participation of all sorts. A breach opened between our bubbles [eyes] like the zipper on a Comme Des Garçon wallet, and like a handful of loose receipts, the following text fell out [muzzle, whiskers].

2017, Oil on linen, 18 x 24 inches (46 x 61 cm)

I’m not a fan of the word bitter when it’s used to describe cold. I feel like bitter is too nuanced, suggests too many of the experiential layers that cold weather so often levels. Nor do I think sour would be better suited, in case you’re wondering. To me sourness involves a duration, the kind of bending temporal vector that cold air breaks into sharp little instants. If there is some umami-esque mystery favor which approximates how severe cold obliterates our mind’s attempts at conscious circumscription [head], I haven’t heard of it. Only pain describes this unique phenomenon and oh how those clear January days press pain through the heaviest goose down boundaries. Then again don’t all descriptions gain traction through repeated use? I guess I’ll just say that a few weeks ago I was stuck outside the Neue Galerie on a bitter cold day.

That morning, from beneath my comforter [muzzle, nose, nostrils], I’d hatched a plan to see the museum’s N. show. At the time it seemed like a good plan for two reasons. First, as I’d woken with a severe hangover I could be certain some color or other was liable to make me cry. The day after a long night of boozing I tend to feel very open to the world’s aesthetic character and I like to take advantage of this by subjecting myself to beauty wherever I can. Second, I thought that after the show I could take in a little hair of the dog at Cafe Sabarsky while pretending to be Walser or Altenberg or any of the other prose bozos whose spirits are invited to hang around for this very purpose.

What I didn’t account for was that my alcoholic porosity left me equally vulnerable to cold weather. I figured this out after about 15 minutes on the corner of 86th and 5th. Towards the end of the wait one particularly icy gust of wind passed through my coat, then through my “self” and rendered my ego as diffuse and temporary as the snow powdering my shoulders [whiskers]. For a few moments I felt as light and blissful as that Bodhisatva rabbit sizzling in old Shakra’s campfire. Luckily the line began moving forward shortly thereafter and I returned to myself when my keys and phone were handed back to me on the other side of the museum’s metal detector.

Up in the galleries the exhibition was up to snuff. Lots of great paintings of faces. Lots of bizarre color decisions and a crazy broad range of paint handling. Some highly competent divisionist daubings were succeeded by landscapes comprised of thin washes of color. These pale forms rarely overlapped and appeared increasingly abstract with each subsequent iteration until ultimately, rendered space became indistinguishable from design, that old foil. The serial attitude carried over into what N. called the savior’s face paintings, in the following room and then shifted into an even higher gear in the near perfect Abstract Heads. I loved the weird stippling technique which made their ombre surfaces appear, for lack of a better word, sandy.

Finally, there was a room – as small and dim as a reliquary- of late works where all the painted heads morphed into more explicit cruciforms and the paintings got tiny and precious and the exhibition’s didactics informed the viewers that N. had arthritis and that icon paintings was a russian thing and death was immanent and blah blah blah.

Afterwards I sat in the cafe and tried to escape the weird feeling the last room left me with. I took out my notebook turned to a fresh page and wrote the date. Something occurred to me but quickly un-occured itself. At a loss I began to eavesdrop on my neighbors who were speaking a language I didn’t understand. Vowels and consonants crashed together around my head. Now and then a cognate bobbed out of the froth. It sounded kind of Portuguese.

I listened until the whole situation started feeling very phatic and ritualistic. Perhaps because I was feeling hungry I imagined us all decked out in ceremonial robes, our long sleeves [ears] wet with the blood of sacrificial oxen. Communication- the act of transmitting a message or meaning – had come unhinged from elocution in a way which manifested God much more effectively than any curatorial prostelytizations.

With divinity now present I was able to get past the cruciforms and address what should have been the obvious structural components the Abstract Heads, their physiognomy. Each painting had scrunched up eyes, and a gaping smile. They were laughing of course! A group of laughing paintings! What was abstract in the abstract heads was not the head. I mean what was abstract was not some unique human abstracted into general shapes but rather a collective human voice abstracted – through the technique of serial repetition – into visual matter. Facing these paintings I became a seismographer, someone who ‘hears’ the world’s vibrations with their eyes, by admiring some device’s crooked output [philtrum]. I wrote in my notebook: “Idea for a show. N. paintings. Laugh track.”

A waiter appeared and I ordered some stuff. When my food arrived I surveyed the tableaux like a condor. My foamy pilsener and the Chesnut Soup with Viennese Melange looked like a pair of creamy moons [eyes]. The big juicy bratwurst [mouth] smiled up at me. I ate and ordered another beer and some more snacks. By the time the check came I’d consumed enough for two, so I put the bill on the credit card I reserve for business expenses. Then in my journal I made my most significant note of the day. It read, “Lunch meeting with editor”. Thats right, I’ll risk no dark stains [pupils] upon my reputation with the IRS!

2017, Oil on linen, 60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114 cm)

Once painting was the highest art. It came from the eye and its neighbor the brain [muzzle]. Sculpture, painting’s subordinate, was the stuff of hands and their neighbor the anus [nose, whiskers]. The distinction between high and low was policed. Each egg had its own basket [eyes, pupils]. This was long before kitsch existed mind you. Later on Duchamp pointed out that the hand bridged the gap between the anus and the eye. He suggested shutting the eye, effectively quarantining art inside the brain. But the quarantine made everyone crazy so for his final work Duchamp built a stage [head] and enlisted the eye’s participation in a dramatic reconciliation of art with the anus. The hands played an accompaniment at the ends of their tired arms [ears].

2017, Oil on linen, 60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114 cm)

It’s not true. I did not care about the dead mouse on the sticky trap [head]. Why? Because life is interesting. There are dark interests like lead weights [pupils] that tug tug tug, and light interests like balloons [ears] that accrue coo coo. In point of fact, they say the only truly disinterested party is death. Furthermore they say that it only seems greedy because we are projecting. They say if death ever takes you in its jaws you ought to use its uvula [eyes] like a speed bag. This is great exercise and do it for twenty minute intervals with five minute breaks on death’s broad papillated tongue [muzzle, whiskers]. One interest of mine is people with “nice arms” [nose, mouth]- in how to join their ranks that is – and they say this regimen is the only way.

2017, Oil on linen, 60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114 cm)

It’s not true. My dad is around. He’s an architect of several prominent health care facilities. The two most prominent are famous for their dome structures and dark foreboding entry halls [eyes, pupils]. The least prominent is a rectangle [head] he staked out in a disused ball field in Great Neck. It’s not a hospital as far as I can see but for some reason it appears on his C.V. My dad’s interests include theatre and cocktails, also England now and America before he was born. He likes to vacation with my mom, and in their travels, photographs roofs [mouth]. I’d say my dad is a good dad because I am rarely, if ever, aware of his ego. Once I ironed all the dollar bills I’d saved up and wrapped them in a rubber band from the rubber band ball (muzzle/ whiskers) which clogged our kitchen drawer. I took the stack of bills to church and showed them to a kid who took me to see a mouse on one of those sticky traps that he pulled with his toe from under a radiator. It’s tail was split into two pieces (ears). There was a spot of brown blood [nose] near its tiny mouth. My dad consoled me.

2017, Oil on linen, 60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114 cm)

Rinsed some blueberries [whiskers] under the faucet this morning. It went well. A dog bit my calf a few days ago. It went less well.

It’s very swollen and red around the two holes where his fangs stuck me you see [eyes,pupils]. A bee [nose]stung me yesterday afternoon on the finger I use to scratch my head. This wound is swollen too.

A thought creaks in my head like a wagon wheel [head]. Could nature be singling me out for revenge? Jesus. Can she not find a better candidate for mankind-folley-shouldering? Oh, I’ve walked beneath highway overpasses and marveled at the size of their concrete trunks [ears], but I didn’t build them. Yes, I’ve chewed flesh with my teeth and scenery with my eyes, yet no more or less than the other bobble heads.

Perhaps I’ve been selected at random, like the blade of grass [mouth] in the famous golf ball [head] analogy. What are the chances! Or perhaps I come recommended by the mackerel, who I met on a dock in Maine, and through whose brain I slipped the slender paring knife.

2017, Oil on linen, 60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114 cm)

My interests are many and varied. I am interested in things large and small. If I’m at a circus I am interested in the ring and the hoola hoop [head, muzzle]. On the street I am interested in all of the cutting edge boot styles though I lean towards the forms which we of as think of as “classic” [pupils]. When I listen to the radio I am interested in the proposed solutions to all sorts of political and economic problems. However I am also interested in the peanut shaped silence [eyes] which surrounds the problems we think of as “entrenched”. On any evening I might be interested in the string of words in some old book and the unrelated string of thoughts which fill my head. If you show me a scale [ears] I will be interested in the hanging weight and the contents of the pan.

2017, Oil on linen, 60 x 45 inches (152.4 x 114 cm)

In the Brooklyn Museum I seen a little painting [head] what piqued my interest. It was called Art Versus Law and it showed a ruffian in dented hat, a shirt I forget right now, and a pair of tattered slacks [ears]. The man was loaded up with a pallet, some canvases and bunch of brushes [whiskers]. He was locked out of his studio by a heavy iron padlock [nose] and a notice on the door [muzzle] which read “To Let on Good Security”. Seeing this painting really made me think two thoughts. 1. The curator who hanged it is on the side of the artist. 2. The curator who hanged it is against them that make all those glass buildings [eyes]. Now I keep the thoughts on a table. Clack! Clack! Clack! Is the sound when they touch. Oh hush you billiard balls! [pupils] Quiet you useless music!

2017, Oil on linen, 18 x 24 inches (46 x 61 cm)

What do these flies [whiskers] want? What does that butterfly want? [muzzle] What do you call moisture which gets things done? Dew. What does the beetle [nose] want? The mackerel? The lure? [mouth] The flâneur? To hang around. What about the churchyard yew in the Tuesday crossword clue? What does it want? The soft moss [pupils] between its roots? The graves [eyes] in its shade? Hmm.

What does I want? Not much. More than two green beans [ears] if it’s green beans for supper. Oh, and to be loved by everyone. Also maybe to have some type of smooth round disc [head] which I can keep in my underwear drawer.

2017, Oil on linen, 12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 23 cm)

C L E A R I N G